The Rise of the Georgia Blueberry

From native wild bushes to a $350 million annual industry. How the University of Georgia helped the state become one of the top producers of blueberries.

File Under

Bake them in a muffin or pie (don’t forget the ice cream). Top some onto your morning oatmeal or pancakes. Or heck, just pick one straight from a bush and pop it into your mouth.

However, you prefer your blueberries, you’re sure to enjoy it as one of the tastiest (and healthiest) flavors of the summer.

Better still if it’s grown locally in your home state.

Thanks to the blossoming blueberry industry in Georgia—and the scientific foundation that helped build that industry in just a few decades—it’s not too hard to find Georgia blueberries in the peak growing times of late May to early July.

And while Georgia may be in no hurry to shed its Peach State nickname, blueberries are just as important as the peanut and peach crops that the state is known for.

While Georgia ranks third nationally for both blueberry and peach production, the blueberry far outsells its fuzzy cousin, with the blueberry industry contributing $348.7 million to Georgia’s economy in 2021 compared to $84.8 million from peaches, according to the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences’ Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development.

That wasn’t always the case. Like the berry itself, blueberry production started small.

Blueberry production takes root

Georgia’s hot summers make it tough for most species of blueberries to ever thrive, but the rabbiteye blueberry, which can withstand hot weather, is native to Georgia and much of the South.

To make the species more commercially viable, Tom Brightwell, a UGA horticulturist, began breeding wild rabbiteye blueberry bushes in the 1940s and continued until his retirement in the 1970s. After that Scott NeSmith, a professor emeritus in the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences (CAES), took over. He bred more than 40 varieties (including rabbiteye and Southern highbush), focusing on blueberries that could be harvested by machine, were disease- and pest-resistant, and could grow to larger sizes.

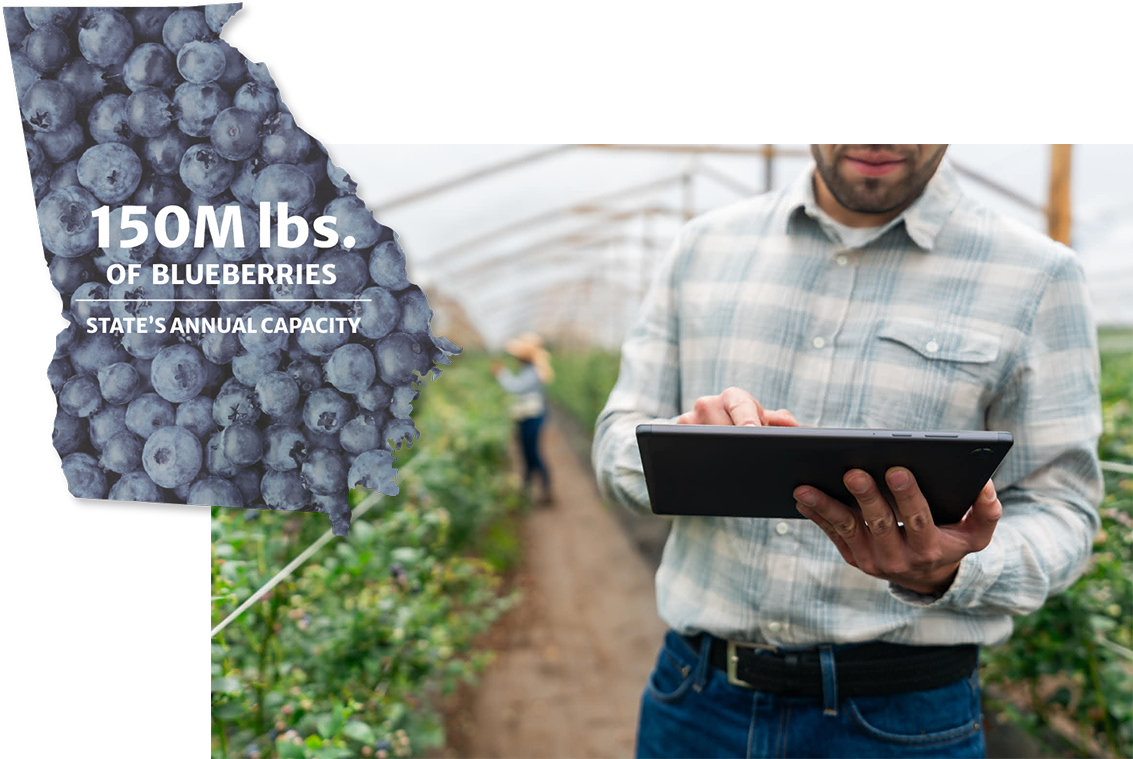

“Our industry is now at a stage where we can produce—given cooperative weather—well in excess of 150 million pounds per year in a good year.”

The work of NeSmith and other UGA faculty in coordination with Georgia growers helped develop the blueberry’s exponential success—well, that and consumers’ growing appetite for the juicy berries.

“Our industry is now at a stage where we can produce—given cooperative weather—well in excess of 150 million pounds per year in a good year,” NeSmith said. “That’s a long way from the 5 to 10 million pounds of the 1990s.”

Beyond breeding

To sustain and even grow upon that success will take more than inventing breeding. Two of the biggest threats to blueberry growing (and to other crops, for that matter) are labor shortages and warming temperatures.

To address labor costs, UGA’s blueberry breeding program, now under the direction of Ye “Juliet” Chu, is breeding and improving plants to produce fruit that is acceptable to consumers and can survive machine harvesting, handling, and packaging.

“Looking forward, we intend to broaden the genetic base of our breeding program through interspecific hybridization and will engage genetic tools to accelerate the breeding effort,” says Chu, assistant professor of horticulture and faculty in the CAES Institute of Plant Breeding, Genetics and Genomics.

But one element neither producers nor breeding experts can control is the weather.

Blueberries require a period of cold to successfully grow, and Georgia is the southernmost state that can support production. However, unpredictable winter temperatures—too hot or too cold—can slow things down.

(L to R: Brightwell, Nesmith, Chu, Rubio)

“Last year we had a detrimental freeze that wiped out almost 50% of the crop,” says

Zilfina Rubio Ames, an assistant professor in UGA’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. Rubio Ames’ research focuses on how to get the best of blueberry crops once they’ve been planted.

“Last year we had a detrimental freeze that wiped out almost 50% of the crop.”

To mitigate unpredictable weather, Rubio Ames looks at improving management practices, including pruning techniques and the use of plant growth regulators, to protect crops from variable climate conditions.

Rubio Ames’ research has one overarching goal, which she shares with other UGA blueberry-focused faculty: to make production more efficient and economically viable for growers, which leads to more blueberries for consumers to enjoy.